Recently there was a post on /r/AskHistorians titled Why was the use of lead and asbestos so widespread in the modern period (and earlier) when their detrimental effects have been known for centuries? The question was posed by UK-based user Fouriels, asked how the common wizdom was there was that the toxcitiy of these toxic materials had been known since ancient times, yet use and poisonings were widespread during the industrial revolution of the 19th century.

I struggle to believe that we collectively somehow forgot that lead/asbestos are toxic – my best guess is that a combination of lobbying and under-education of the population, which resulted in other horrors during the industrial period, would account for this. But i’d like to hear from someone more knowledgeable how these substances really took off (especially in the modern UK period) and caused so much damage, when their effects have apparently always been known.

The user included this quote from the Wikipedia page for lead poisoning:

An important step in the understanding of childhood lead poisoning occurred when toxicity in children from lead paint was recognized in Australia in 1897. France, Belgium, and Austria banned white lead interior paints in 1909; the League of Nations followed suit in 1922. However, in the United States, laws banning lead house paint were not passed until 1971, and it was phased out and not fully banned until 1978.

Go check out the thread if you’re interested in the history of asbestos. I contributed answers relating to lead, especially lead paint mentioning other similarly toxic consumer products that I covered in my talk Dangerous Products. Note that rule #5 of /r/AskHistorians is to “Provide Primary and Secondary Sources If Asked. No Tertiary Sources Like Wikipedia.” Hence my reliance on academic papers and heavy use of quotations, as is common in top level comments in this subreddit.

I am not a historian, but I am a marketer with a MSc in Marketing. One of my specialties is the history of marketing products that were dangerous, whether the companies knew so or not, and the slow legislative banning process.

Lead Paint – Only Banned in 1978 in The US

Banned in some places, but not all

In “Cater to the children”: the role of the lead industry in a public health tragedy, 1900-1955 by Markowitz & Rosner published in the American Journal of Public Health in 2000, the authors confirm what Wikipedia says about the accumulated knowledge of the toxicity of lead, and the slowness of the US to ban lead paint.

By the mid-1920s, there was strong and ample evidence of the toxicity of lead paint to children, to painters, and to others who worked with lead as studies detailed the harm caused by lead dust, the dangers of cumulative doses of lead, the special vulnerability of children, and the harm lead caused to the nervous system in particular. Outside the United States, the dangers represented by lead paint manufacturing and application led to many countries’ enacting bans or restrictions on the use of white lead for interior paint: France, Belgium, and Austria in 1909; Tunisia and Greece in 1922; Czechoslovakia in 1924; Great Britain, Sweden, and Belgium in 1926; Poland in 1927; Spain and Yugoslavia in 1931; and Cuba in 1934. In 1922, the Third International Labor Conference of the League of Nations recommended the banning of white lead for interior use. In the United States and Canada, there were calls for the use of non–lead-based paints in interiors. As early as 1913, Alice Hamilton wrote that “the total prohibition for lead paint for use in interior work would do more than anything else to improve conditions in the painting trade.” By the early 1930s, a consensus developed among specialists that lead paint posed a hazard to children.

Did manufacturers know?

Now, sometimes the question gets asked “did the manufacturers and sellers know?” In the case of arsenic which used in fabrics dyes and colored wallpaper, it was banned in much of mainland europe in the early 19th century but permitted and popular in Victorian England, much to the horror of foreign scientists and politicians. But in England there was a level of ignorance and denial, and many sad stories of sickness and death. (Read the excellent books Bitten by Witch Fever: Wallpaper & Arsenic in the Nineteenth-Century Home, and Professor Alison Matthews David’s Fashion Victims: The Dangers of Dress Past and Present). In the case of lead however, the manufacturers definitely knew.

Markowitz & Rosner (2000) point out that

in 1939, the National Paint, Varnish and Lacquer Association (NPVLA), a trade group representing pigment and paint manufacturers, wrote a letter marked “CONFIDENTIAL Not for Publication,”…informed its members that toxic materials “may enter the body through the lungs . . . through the skin, or through the mouth or stomach.” The letter specifically pointed out that lead compounds such as white lead, red lead, litharge, and lead chromate “may be considered as toxic if they find their way into the stomach.” The NPVLA reproduced for its members a set of legal principles established by the Manufacturing Chemists’ Association regarding the labeling of dangerous products.

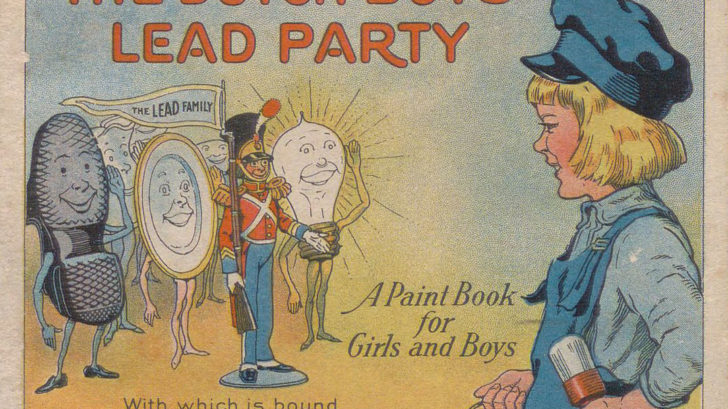

So, basically, they thought they were off the hook legally and morally if they labelled their products as toxic. But then to answer the question about why use was so widespread, we look at the marketing of the product, which promoted lead in everyday home products not just as effective and safe, but “the pigment industry emphasized lead paint’s “healthful” qualities.” Their marketing campaigns targeted both adults and kids. The best example of this is an early 1920s coloring in book and poem called “The Dutch Boy’s Lead Party” which was given away with catalogs along with some watercolor paints. I could document 50 years of lead industry marketing, but this is truly the most egregious. Of all the links here, read this. It’s short and shocking.

To confirm the point about consumer ignorance, Markowitz & Rosner (2000) mention that in 1943 Time magazine reported on an article by pediatricians Randolph Byers and Elizabeth Lord in the American Journal of Diseases of Children (“Paint Eaters,” Time, 20 December 1943, 49). Quoting Time, Markowitz & Rosner (2000) noted that

parents’ lack of understanding of the dangers of lead-based paint led many to use this toxic material on toys, cribs, and windowsills.

In response, the The Lead Industry Association (LIA) did what we now famously know the Tobacco industry did (and wonderfully demonstrated in the movie and book Thank You For Smoking (trailer) Markowitz & Rosner (2000) note that they

maintained that the assumption regarding the relationship between lead poisoning in early infancy and later mental retardation had not been proven and that many of the cases of lead poisoning had “never been conclusively proven.”

Sewing doubt

In 2007 Rosner and Markowitz followed up with anpother excellent paper in the American Journal of Public Health titled The politics of lead toxicology and the devastating consequences for children in which they document and explain three primary means that were used to undermine the growing body of evidence of the toxicity of lead.

In the 1920s, the General Motors Company, with the aide of DuPont and Standard Oil Companies, established the Kettering Labs, a research unit at the University of Cincinnati which, for many decades was largely supported by industry funds. In the same decade, the lead industry sponsored the research of Joseph Aub at Harvard who worked on neurophysiology of lead.

A second way was to shape our understanding of lead itself, portraying it as an indispensable and healthful element essential for all modern life. Lead was portrayed as safe for children to use, be around, and even touch.

The third way that lead was exempted from the normal public health measures and regulatory apparatus that had largely controlled phosphorus poisoning, poor quality food and meats and other potential public health hazards was more insidious and involved directly influencing the scientific integrity of the clinical observations and research. Throughout the past century tremendous pressure by the lead industry itself was brought to bear to quiet, even intimidate, researchers and clinicians who reported on or identified lead as a hazard.

If you’re not looking to read a lengthy scientific paper, this 2013 article in The Atlantic by Rosner and Markowitz titled Why It Took Decades of Blaming Parents Before We Banned Lead Paint summarizes their two aforementioned papers in a shorter form.

Also worth noting, it wasn’t just interior finishes. Painted children’s toys were a huge problem too, catastrophically for kids at an age when they’re chewing on them compared to the mere disaster of just handling them.

In addition to these two academic papers, I highly recommend the books Quackery: A Brief History of the Worst Ways to Cure Everything by medical doctor Lydia Kang and Nate Pedersen, and the aforementioned Fashion Victims by Allison Matthews David, an associate professor in the School of Fashion at Ryerson University. Both of these are well researched and provide a multitude of excellent references, and they have excellent chapters on lead. However as you read about other toxic substances, patterns emerge, which include public denial, public ignorance, scientific corruption and undermining and doubt casting by manufacturers, knowledge of toxicity but apathy at the suffering of lower cases who get the higher dosages (from “who cares if slaves go insane and die mining lead”, to “who cares if my seamstress suffers”), and the glacial pace at which the legislative process has always run at.

Leaded Gasoline – Only Phased out Starting in the 1970s in The US

One user asked “During your research in that history did you come across similar material on the use of lead in plumbing and gasoline? …I recall some reports on research that concluded exposure to lead from that source may have been even more responsible for lead contamination affecting children than lead paint. But up until the movement to ban its use, do you have any information on how much counter marketing was being done to make it sound safe to use?”

I didn’t research plumbing much, as it was less a marketed consumer good, and more something that was installed by cities, house builders, and plumbers.

As for paint vs gasoline toxcity, I have no hard data directly comparing the two, but my gut feeling is that gasoline had the much greater impact.

See Reyes (2007). Environmental Policy as Social Policy? The Impact of Childhood Lead Exposure on Crime. To quote the non-technical summary

Reyes tests the hypothesis that higher childhood lead exposure is associated with adult criminality. Her estimates suggest not only that childhood lead exposure may lead to higher violent crime rates, but that a large portion of the decline in the U.S. violent crime rate between 1992 and 2002 may be attributable to reductions in gasoline lead exposure.

Prevention, between 1976-80 and 1998-2002 average blood lead levels in children aged 1 to 5 decreased from 15.0 to 1.9 micrograms per deciliter.

The results suggest that a 10 percent increase in the grams of lead per gallon of gasoline leads to a 7.9 percent increase in violent crime…From 1992 to 2002, violent crime dropped 34 percent. Reyes estimates that declining lead exposure was responsible for a 56 percent decrease in this time period.

The author concludes that lead’s effect on violent crime may be just the tip of the iceberg. Increases in impulsivity, aggression, and ADHD can affect many other behaviors such as substance abuse, suicide, teenage pregnancy, poor academic performance, poor labor market performance, and divorce, suggesting that environmental policy can have far reaching effects on social outcomes.

According to this UN-backed study

The UN World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that between 15 and 18 million children in developing countries currently suffer from permanent brain damage due to lead poisoning and, according to the results of the research, leaded petrol was responsible for some 90 per cent of human lead exposure.

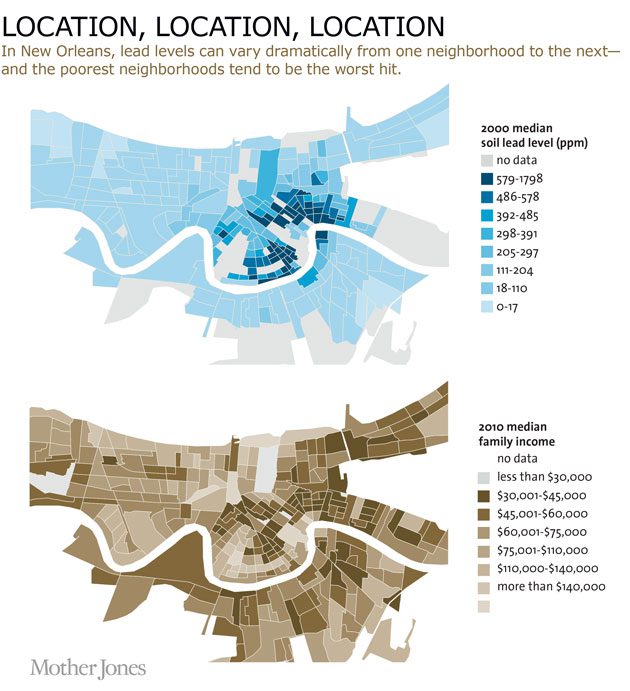

For further information, I highly recommend Lead: America’s Real Criminal Element on Mother Jones.

As for counter-marketing promoting it as safe, I highly recommend this journalistic article A century of tragedy: How the car and gas industry knew about the health risks of leaded fuel but sold it for 100 years by Bill Kovarik, Professor of Communication, Radford University.

The auto and gas industries’ attitude toward the media was hostile from the beginning. At Standard Oil’s first press conference about the 1924 Ethyl disaster, a spokesman claimed he had no idea what had happened while advising the media that “Nothing ought to be said about this matter in the public interest.”

More facts emerged in the months after the event, and by the spring of 1925, in-depth newspaper coverage started to appear, framing the issue as public health versus industrial progress. A New York World article asked Yale University gas warfare expert Yandell Henderson and GM’s tetraethyl lead researcher Thomas Midgley whether leaded gasoline would poison people. Midgley joked about public health concerns and falsely insisted that leaded gasoline was the only way to raise fuel power. To demonstrate the negative impacts of leaded fuel, Henderson estimated that 30 tons of lead would fall in a dusty rain on New York’s Fifth Avenue every year.

Industry officials were outraged over the coverage. A GM public relations history from 1948 called the New York World’s coverage “a campaign of publicity against the public sale of gasoline containing the company’s antiknock compound.” GM also claimed that the media labeled leaded gas “loony gas” when, in fact, it was the workers themselves who named it as such.

Ironically, according to the BBC

Midgley was – perhaps – being a little disingenuous. He had recently spent several months in Florida, recuperating from lead poisoning.

History Repeating

They say, “those who don’t know their history are destined to repeat it, and those that do are destined to watch it happen all over again.”

What we saw with lead, asbestos, tobacco, mercury, thallium, arsenic, hydrogenated margarine, saturated fats, and…oh the list goes on, we are now seeing with sugar, other food addatives, vapes, PFAS, flame retardants, microplastics in detergents, silver in clothing, and….oh the list goes on.

If you’re interested in watching my 1 hour talk on the topic + Q&A, visit dangerousproductstalk.com.