As a teenager in the mid-2000s, I was a massive fan of Nine Inch Nails. Though I wasn’t totally aware of it at the time, the band’s marketing tactics had a great influence on me and really kickstarted many years of CD and concert DVD collecting.

Though I haven’t really followed the band closely in recent years, I still have a great deal of respect for the interesting tactics Trent Reznor has been using over the years and seeing the kind of things he’s doing to promote his new albums and tours.

Numbered Discography

From the very first single “Down In It” in 1989, Nine Inch Nails implemented a numbering system for all of their releases. Each release has a “Halo” number, with Down In It being Halo 1. This was inspired by the numbering system Depeche Mode was already using for their singles, which was something they only started doing with their 6th single “Leave in Silence” which was listed as “Bong 1”.

As Nine Inch Nails started re-releasing updated versions of albums, these had adjusted Halo numbers so that they would not replace the original releases. For example, the remastered version of Halo 2 – Pretty Hate Machine was Halo 2R, intended to sit next to the original release on your shelf.

By numbering the albums on the spines of the cases, it encourages completionist to make their shelf look complete by buying every single, EP and live album, not just the main studio albums.

Hidden Tracks & Bonus Discs

The Broken EP was originally released with an extra 3″ CD or 7″ record containing two bonus tracks “Physical” and “Suck”. These tracks were both covers the band liked to play live but did not thematically match the rest of the EP. Later versions of the EP included these tracks as hidden tracks following 97 1-second tracks of silence. A relic of the physical disc era, this is something that wouldn’t work today.

Different tracklists in different countries

This is not unique to Nine Inch Nails by any stretch and is common to many, if not all major international artists, but not much seems to be written about why the same album will have a slightly different tracklist around the world.

Broken movie

TVT, the original record label to sign Nine Inch Nails had expected Pretty Hate Machine to be a lot more radio-friendly, and therefore more profitable. This caused a lot of tension that led to Trent writing the Broken EP which was released on his next record label Interscope. This EP had a much harsher, angrier tone than the previous album and was effectively a product of his frustration with the previous label.

To accompany this, a 20-minute film called The Broken Movie was produced by Peter Christopherson of Cole and Throbbing Gristle in 1993. The film was effectively a very realistic fake snuff film that weaves in footage of the music videos from the EP together. The result was so unsettling that they mutually agreed not to release it.

It was shared amongst Reznor’s friends on VHS, with certain scenes blacked out in each version of the video. This would allow Reznor to know who would leak it to the public, which inevitably did happen.

Fans dubbed copies from copies of this video, further deteriorating the quality of the footage and making it seem even creepier. In a pre-internet era, it would have been something truly satisfying to hunt down in a physical format. Many fans would stumble across it at swap meets and conventions not knowing what they were about to see, as information about this was scarce.

Something as mysterious and notorious as this would not deliver the same experience today. With bittorrents and other methods of sharing files, it will be difficult for anyone to ever achieve viral sharing of a physical medium like VHS tapes again.

Fancy CD Packaging

Most of the releases by Trent Reznor and Nine Inch Nails will be something beyond the typical cheap jewel case most other albums are produced in. Many are some form of digipak or other interesting cardboard cases.

As an Australian fan of Nine Inch Nails, there’s a fascinating interview from right after the disastrous Melbourne concert in 2007 that I attended. I loved this article so much, I kept a copy of it for many years, and while I must have thrown it out or lost it in recent times, it’s still available on their website.

It talks about how he was shocked to see that all his products, including his latest album at the time, Year Zero, cost an extra $10 AUD than other new releases. He grilled his studio executives about this and the executive said that it’s because his packaging costs a lot more. Reznor then said that the album, complete with colour changing ink in the disc costs him an extra 83 cents each, which he fronts out of his own pocket, not the record label. The executive then said “Basically it’s because we know you’ve got a core audience that’s gonna buy whatever we put out, so we can charge more for that. It’s the pop stuff we have to discount to get people to buy it. True fans will pay whatever.”

It’s really no surprise he wanted to get away from his record label.

Experimenting with Alternate Reality Gaming (ARG)

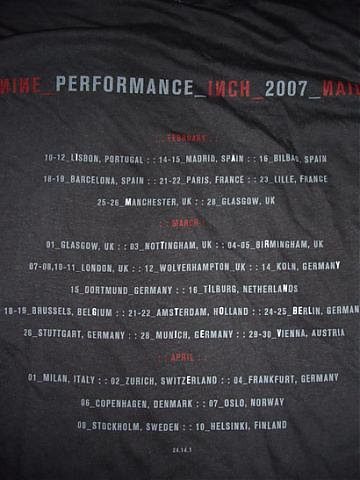

The 2007 concept album Year Zero featured a fascinating campaign that blended in both real-world and online activities. It started in February where fans who attended the European tour noticed bolded letters on the back of their shirt amongst the tour dates. It spells out “I’m trying to believe” which would turn out to be a lyric from a song on the upcoming album.

Googling this phrase then lead to a website that warns of a fictional drug called “Parepin” that relates to the story of the concept album. Further Googling of Parepin lead you to other websites made for this purpose. These sites talk about a conspiracy about the government putting Parepin in the water. There were also email addresses you would find that would auto-reply messages to you if you emailed them, “It is now clear to me that Parepin is a completely safe and effective agent. I’m drinking the water. So should you.”

There were also phone numbers to call, wiretap transcripts to read and at a few concerts, USB sticks were found with tracks from the unreleased album were found, which allowed fans to leak the new audio online.

This campaign was run by 42 Entertainment and Reznor rather than the record label.

Year Zero Campaign from an SEO perspective

This campaign was so interesting from a viral marketing perspective that Matt Cutts of Google blogged about it, describing it from an SEO point of view. He praised the use of made-up words like Parepin that would be unique to the campaign and easy to find in Google and that whilst the websites had animated effects on the text, it was still real text in the source code the page, meaning Google could read it and index it.

He also said that by allowing fans to find these clues, USB sticks etc, the links obtained to the websites in this campaign were totally organic, rather than the usual spammy PR associated with most new album releases.

The main flaw he pointed out was that several of the websites were all hosted on the class C subnet, meaning if fans knew how to do a reverse IP search, they would find a list of the other sites owned by this company and could take a massive shortcut rather than following the intended path of clues.

For example, if you do a reverse IP lookup for this website, you will see other websites I own plus many others who are also sharing the same cheap hosting I am currently using. Granted back in 2007, far fewer people would have known how to do this.

Speaking of the various websites built for the campaign, whilst these are all offline now, some of them have a 302 redirect to the campaign page on the 42 Entertainment website. These websites obtained really good metrics that 42 Entertainment should try and leverage to help their own SEO Rankings.

|

Domain |

DA |

Spam |

Trust Flow |

Citation Flow |

Trust Ratio |

Referring Domains |

|

39 |

1% |

14 |

16 |

0.88 |

247 |

|

|

30 |

1% |

7 |

13 |

0.54 |

101 |

|

|

25 |

1% |

7 |

13 |

0.54 |

87 |

The metrics of these sites are quite good. 42 Entertainment should probably change these to 301 redirects instead of 302 to greater benefit their own website. Leaving it as 302 forever is wasteful.

Embracing Digital & Free Music

Once free of his label, Reznor absolutely went to town on releasing music and promoting it in incredibly modern ways that very few other major artists had done before. Having been notorious for long delays between albums, usually about 5 years, 2008 had not one, but two albums released just four months apart, Ghosts I-IV and The Slip, which won Nine Inch Nails a Webby Award for Artist of the Year.

Ghosts I-IV

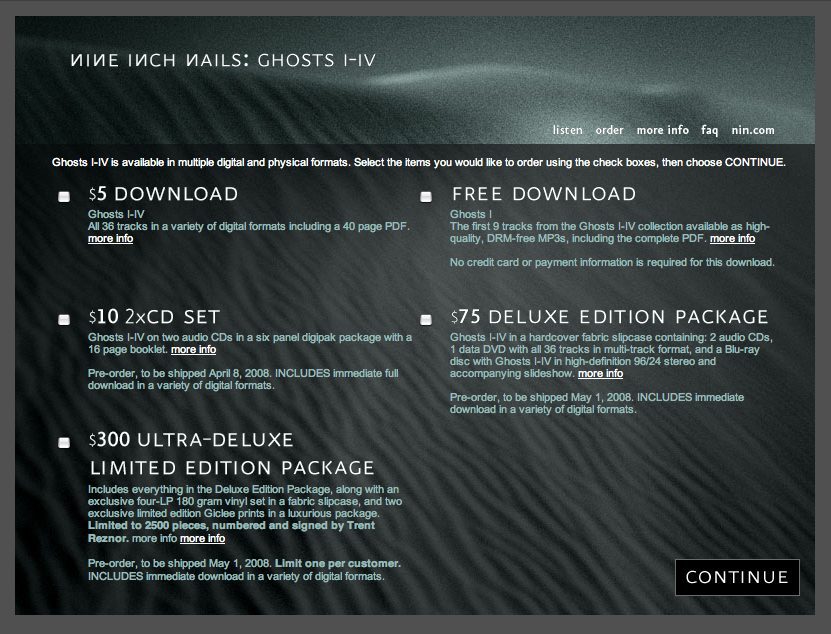

The four-part, 36-track instrumental album Ghosts I-IV had its first part available for free via BitTorrent. Yes, BitTorrent, the scourge of the entertainment industry.

You could then also buy the full album as a digital download for just $5 USD from either Amazon or the Nine Inch Nails website, nin.com, which became so popular, he had to rapidly upgrade his hosting.

Fans who wanted to add a physical copy of Halo 26 to their shelf could buy Ghosts I-IV as a two-disc album for $10 USD and there were also special editions available for $75 and $300 USD. The $300 version sold out in the first 24 hours.

Another interesting thing about this album is that each track featured different artwork when playing the MP3 files.

Some of the higher-end packages came with the digital assets which allowed purchasers to remix the music under Creative Commons licensing. Usually, bands and record labels make it difficult to get the raw assets for doing remixes unless it’s been commissioned officially.

Interestingly, in 2018 viral country/rap hit “Old Time Road” by Lil Nas X sampled a clip of “34 Ghosts IV” without clearance from Reznor. Management freaked out about this when the song started to gather steam, but luckily he was cool about it all.

The Slip

This album was notable for being recorded in just three weeks, with it’s first and only single “Discipline” being distributed via email to radio stations less than 24 hours after being mastered. This kind of speed would have been impossible under his old record label. And like Ghosts I-IV before, it this was released for free online digitally under Creative Commons license on nin.com and included several DRM-free audio formats. Again, the raw files made available so that fans could remix the tracks themselves for non-commercial use.

A limited physical release of 250,000 units was released a few months later and included a DVD of live rehearsal videos of the band practising the new songs from this album.

How To Destroy Angels (2010)

Side project with this wife Mariqueen Maandig Reznor, How To Destroy Angels also got the free album treatment. They released a single exclusively on “A Drowning” on Wired Magazine’s iPad app. A music video was released on pitchfork.com. Clips of their recordings were also shared on Vimeo and YouTube. The 6-track album was then made available for free digitally. The band was then also available to answer questions to fans via Facebook and Tumblr.

This was a great example of “social” marketing, dropping content and being available in the places that their fans were active. Whilst giving away music for free he is also collecting email addresses which he can use to

Bad Witch (2018)

This 30-minute album was released as an “LP” rather than an “EP” so that it would stand out on streaming services such as Spotify, where singles and EP’s get hidden below albums and get fewer listens. This was a way to optimise the new music for listens. They were sure to sell the physical album at a cheaper price like you would an EP, so not to rip off fans.